I suppose I should preface this post by pointing out that

while I may seem to have criticisms of a lot of the readings that does not mean

that I find them to be without value. I've enjoyed most of the readings, and

have found great value in much of what we've looked at.

This reading, in particular, has left me feeling incredibly

uneasy. Black Wealth, White Wealth

co-authored by Melvin Oliver and Thomas Shapiro, had a few moments that felt

contradictory to me. At times it seemed to recognize the ways in which Black

folk in the US have been, and continue to be, marginalized and oppressed in an

anti-Black, White Supremacist society. But then, and mainly at points where

they cite (in a praising manner to boot) William Julius Wilson, it seems like

they devalue the power of racial discrimination and the ways in which it

presently affects the life of Black folk. Because these are the moments that

caused me the most difficulty while reading the text, these will be the moments

that I will focus on in this blog post as it seems less crucial to spend time focusing

on points I understood and agreed with.

But, first:

Are we surprised at the lack of inherited wealth in the

Black community? Especially when we currently live in a time where we are

trying to move “beyond” race without truly confronting our history? We will

forever be haunted by the ghosts of the past if we continue this foolish hope

of moving “beyond” it. Is it a surprise that repression of the Black

communities continues, although through somewhat different means? Same ends,

though. Different means, same ends.

It is possible that the first several pages ruined the rest

of the text for me. For no matter how far away I got from page 7 my mind still

went back to it, thinking “how could these authors support such a statement?

How could they provide it without comment? How can I consider the rest of the

arguments when they are potentially working from a destructive framework?”

The passage that I am referring to is on page 12 (.pdf page

7). They introduce an incredibly problematic William Julius Wilson quote by

saying he provides an “eloquent and influential...” statement:

The argument for class, most

eloquently and influentially stated by William Julius Wilson in his 1978 book The Declining Significance of Race,

suggests that the racial barriers of the past are less important than

present-day social class attributes in determining the economic life chances of

black Americans…Discrimination and racism, while

still actively practiced in many spheres, have marginally less effect on black

American’s economic attainment than whether or not blacks have the skills

and education necessary to fit in a changing economy. In this view, race assumes importance only as the lingering product of

an oppressive past. As Wilson observes, this time in his Truly Disadvantaged, racism and its most

harmful injuries occurred in the past,

and they are today experienced mainly by those on the bottom of the economic

ladder (12, emphasis mine)

…

Immediately after reading that I

took to Facebook and shared that passage with a like-minded friend of mine. He

immediately replied with “good old wjwilson” and when I said I hadn’t heard of

him before he pointed out that I was probably better off before. This man,

William Julius Wilson, is considered by many to be the leading sociologist on

race and these are the kinds of arguments he puts forth? That certainly makes

me worried for Sociology as a discipline.

Even now, several days after having

read that particular portion, it’s difficult for me to calm the rage brewing

inside so that I may adequately express by disfavor with this excerpt. The

problem is….where do I even begin? The statement itself is easily read as

contradictory to anyone with even an iota of critical race theorizing capabilities.

Discrimination and racism is exactly WHY many Blacks do not have the “skills

and education necessary to fit in a changing economy”. To imply that anti-black

racism is primarily something of the past is incredibly naïve, and perhaps

willfully ignorant. If anti-Black racism was truly a thing of the past, if we as

Black folk in America today are simply living in this society feeling the residue of past racial discrimination, there

would be far less Black death at the hands of the state. There would no longer

exist job discrimination on the basis of race. Michelle Alexander would never

have had to write The New Jim Crow.

And why does she call the prison system The

New Jim Crow? Because we have not attended to our past and due to that we

are fated to continue to exist within a cycle of repetition! And how can we

even begin to attend to our past when “leading sociologists” like Wilson refuse

to acknowledge what is happening (what is TRULY happening) in there here and

now?!

Race assumes importance only as the lingering product of an oppressive

past.

I just can’t even begin to

address that sentence. The steam coming out of my ears makes it nearly

impossible to type a full sentence.

The majority of these chapters

discuss the ways in which middle-class Black folk are essentially treated as if

they are “lower-class”. This is how race is classed (and one could make an

argument for ways in which class is also raced, but I will not attend to that

at this moment). Sure, “racism and its most harmful injuries occurred in the

past, and they are today experienced mainly by those on the bottom of the

economic latter” (12). But racism and its PLENTY harmful injuries are still occurring

in the here and now, while we continue to be haunted by the past, and this is experienced

by all Black folk regardless of where they fall on the economic ladder. But,

let’s not forget, regardless of where they fall on the economic ladder they

might as well be at the very bottom rung of said ladder.

It is beyond my comprehension why

people cannot see the ways in which class is used as a tool to further

anti-Black racism and Black suffering. Why must we try and separate these

things, or to place class as the heavier weight? It’s unproductive and it

ignores the specificity of Black suffering.

Later, on page 34, Wilson appears

again to help bolster the authors’ argument:

The emphasis on

race creates problems of evidence. Especially in the contemporary period, as

William Wilson notes in The Declining

Significance of Race, it is difficult to trace the enduring existence of

racial inequality to an articulate ideology of racism. The trail of historical

evidence proudly left in previous periods is made less evident by heightened

sensitivity to legal sanctions and racial civility in language.

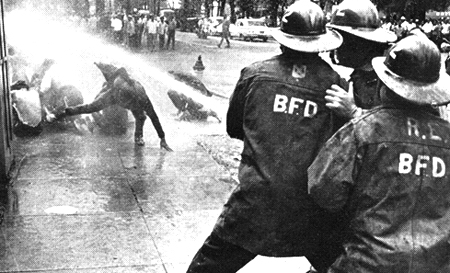

Of course, the long list of Black bodies killed by

state sanctioned “human hunters” (Martinot and Sexton, “The Avant-Garde of

White Supremacy”) simply for existing in their bodies, doesn’t reflect an “articulate

ideology of racism”. It seems as if what is needed are signs saying “Whites

Only!!” and lynching during lunch breaks for some people to see that anti-Black

racism is very much still alive and strong as ever. In response all I

can do is quote at length a portion of Steve Martinot and Jared Sexton’s “TheAvant-Garde of White Supremacy”:

Under conventional definitions of

the government, we seem to be restricted to calling upon it for protection from

its own agents. But what are we doing when we demonstrate against police

brutality, and find ourselves tacitly calling upon the government to help us do

so? These notions of the state as the arbiter of justice and the police as the

unaccountable arbiters of lethal violence are two sides of the same coin.

Narrow understandings of mere racism are proving themselves impoverished

because they cannot see this fundamental relationship. What is needed is the

development of a radical critique of the structure of the coin (170).

I quoted this particular passage in response

because of the way in which Oliver and Shapiro seem to imply that “legal

sanctions” and “racial civility in language” somehow works to make the impact

of racism less felt. And the fact that the majority of this reading consists of

examples of how policy has worked to discriminate and oppress Black folk, but

then they also seem to champion the ways in which policy can help. No. We don’t

need policy. What we need is a radically new structure or else we will continue

to play out the same exact story again and again.

Why do I spend so much time discussing violence? Because State violence and the quotidian nature of racism that Black folk face every single day has a direct impact on their class status and the way in which they are viewed and treated in society. The fact that these chapters do not even begin to address the prison system or other forms of state violence greatly disappoints me. And it shouldn't just be a chapter in the book. It is relevant to many of the points that they bring up (uhm, hellooo, being a "felon" definitely has an impact on the accumulation of wealth, and that's just one easy way they could've tied the prison system in) and yet they are incredibly quiet on the issue. The text was originally written in the late 90s, and so it would be plenty relevant to them to have mentioned these things. And yet they didn't. Perhaps they threw it all into one chapter, but a "very special episode: chapter edition" is not good enough. We can't have a truly productive and full conversation of Black suffering and Black class/racial inequality if we ignore the points I have brought up.