I’m not quite sure how to properly label this post so I’m

leaving it blank. I think this will be somewhat of a reflection post, even

though it’s not on our list of post formats to choose from.

I found the two chapters assigned to us from Barbara Jensen’s

Reading Classes: On Culture and Classism

in America to be quite…interesting. I definitely learned a few new things

that I thought were fascinating (like the entire section on language), but

there were also a few moments where I just couldn’t completely feel (to know!) what she was saying.

Before I completely dive in I’d like to first just quote her

definition of class and classism, mostly for my own benefit so that I have her

definition written in a somewhat permanent space, but also for my peers’

benefit for anyone who has not yet been able to read the text or who simply

missed it:

Class is an

injustice that says some Americans deserve much more time, leisure, control,

and far more financial reward than others. Classism is the set of myths and beliefs that keep those class divisions

intact, that is, the belief that working class cultures and people are

inherently inferior and that class itself demonstrates who the hardest workers

and the rightful winners are (31, emphasis Jensen’s).

I found her definition of class/classism to be quite

interesting because it differs a bit from what we’ve heard before. Not so much

the classism part, but definitely the class definition. With a quick glance it

would also seem as if her definition of class was created simply to bolster her

definition and argument surrounding classism.

But, if we are to think about it a little longer, it becomes much clearer that

her definition of class is not there simply to serve the purpose of her

argument about classism but rather to highlight the inequalities inherent in a

system that stratifies in such a manner. Class is hierarchical, because of that

ordering it means that some folk will be on top (superior) and others will be

on the very bottom (ultimate inferiors). To have, and embrace, such a system

that categorizes in such a way is to embrace inequality. That is what

capitalism does. It produces, and embraces, inequalities. It thrives

on inequality. For if there were no lower classes then how could there be a

capitalist class? The capitalist class needs the working class because they

need a class to manipulate, exploit, and dominate.

Later in the same chapter (“The Invisible Ism”) Jensen goes

on to posit what she believes to be the most “common form of classism [which]

is solipsism, or

my-world-is-the-whole-world”. Of course this is one of the most common, and

pervasive, forms of classism. It is a necessary tool in order to ensure that

class, beyond simple economics, exists. I made a note of this in my last blog

post: colonizers are like viruses. Generalize a bit and switch in “oppressor”

for “colonizer”. The key to ensuring that the life of the oppressor will

continue is to replicate the oppressor’s beliefs in the bodies of those outside

of the oppressing class. The oppressing/dominant/ruling/capitalist class is a

statistical minority! They cannot continue to oppress if they have not caused

others to internalize classist beliefs. In order to insert these new beliefs

the oppressor must erase what once was. If the structure is created to suit the

middle-class, then others have to either adapt or not play the game. In order

to adapt they must shed some of their own identity so that they may take on

some of the oppressor’s identity. This is erasure. Solpsism causes erasure of

identity and deracination.

What I find a bit funny, in an interesting way, is that while

Jensen brings up, and condemns, a concept that brings my mind to erasure, she

somewhat commits the act herself. She continuously mentions “ethnic identity”

or “racial identity” but never really spends any time there. And I don’t expect

her to, but that’s because I am jaded. However, her attempts at inclusion, at

least in these two chapters, often stop after she makes note of “ethnic

identity”. She often continues to make broad-based statements about the

working-class without a true acknowledgment that most of her studies and

observations (or at least the theoretical perspective that she is using to

analyze these observations) are not inclusive of POC. Perhaps there was a

general disclaimer in the introduction section of the book that I may have

missed, as I did not go above and beyond and read more than what was assigned

(although I do try to read introductions/prefaces, but I just did not have the

time).

To give an example, as so far I have mostly been speaking in

generals, let us turn to chapter 3 (“Belonging Versus Becoming”):

For those who

cross the class divide, almost everything about the process asks you to forget

what you knew before. How does one speak of, or grieve, a place that isn’t even

on the map? Invisible, voiceless, unacknowledged—how does one remember what to remember?

(53).

Jensen

had the perfect opportunity at this point to discuss the way in which race is

classed, and the multiple marginalities when it comes to class and people of

color. For people of color crossing class lines even more must be forgotten

(although it is not truly possible). For those whose skin marks them as being

of a lower class even more must be stripped in order to really cross class

lines. And then the question remains as to whether they can ever truly do so. For in the end it doesn’t

matter quite how much agency one speaks with, or whether they can quote Derrida

at length; they will forever walk around with a blatant class marker, one that

cannot simply be unlearned or hidden away back home.

It wasn’t until a bit later in the chapter that the

realization that perhaps Jensen is one of those ‘post-racial’ people popped

into my head (she’s clearly not. She’s simply just not the best at inclusivity,

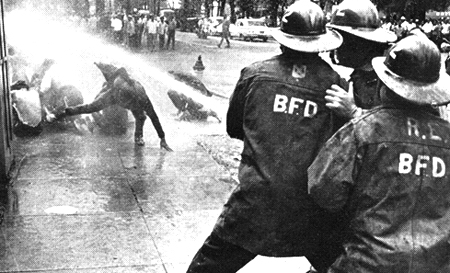

either). On page 62 Jensen states that “when the working class has organized

for better economic treatment, as it often has in American history, it has done

so in spite of deep ethnic, geographic, gender, and color differences, forging

a new and larger sense of ‘us’”. Now…I just didn’t know how to take that. It

seems purposefully naïve. And through that naivety she also erases the

difficulties of past mass class movements where “togetherness” just wasn’t

happening, or at least wasn’t happening without a huge fight and many deaths

and even more jailed. It’s as if she is purposefully false-remembering the

past, and unfortunately by doing so she commits an act of erasure. I’m not the

most well-read on class movements but recently I have been reading Robin D.G.

Kelley’s Hammer and Hoe: Alabama

Communists during the Great Depressing. At times reading about the ways in

which the White southerners, those of whom would benefit very much from the

Communist Party and others like them at the time, were filled with such

spiteful hatred just pained me. There was no “us” in their minds, at least not

a broader class “us”. That is not to say that the Alabama Communists were not

able to come together…eventually. But to put it as simply as “when the working

class has organized…in spite of deep ethnic…and color differences, forcing a

new and larger sense of ‘us’” erases the difficulties and actual BLOOD shed to

make it happen. Of course, there is only so much room in a book so I may be

unfairly criticizing Jensen here.

My last critique is less of a critique and moreso genuine

confusion. How is it that Jensen could attribute the epistemological framework

of what is essentially “connected knowing” (what she calls “emotional”

knowledge/wisdom) to being a phenomenon of the working-class? It just seems to

not account for things like socialized ways in which the genders are taught to

learn. In “Procedural Knowledge: Separate and Connected Knowing” Mary Field

Belensky, et al., posit that:

Separate and connected

[are used] to describe two different conceptions or experiences of the self, as

essentially autonomous (separate from others) or as essentially in relationship

(connected to others). The separate self experiences relationships in terms of “reciprocity,”

considering others as it wishes to be considered. The connected self

experiences relationships as “response to others in their terms” (236).

Does

this not sound quite familiar to the ways in which Jensen separates the epistemologies

of the working and middle class? And yet Belenky et al stated that “separate

and connected knowing are not gender-specific. The two modes may be

gender-related. It is possible that more women than men tip toward connected

knowing and more men than women toward separate knowing” (236). This is due to

socialization. Once things are engrained in us enough they begin to seem

natural (they are naturalized). Perhaps

this, instead of class differences, explains why the couple she mentions on pg

60 were having such trouble. The husband wanting the wife to use more words and

just be explicit with her feelings/thoughts whereas the wife is communicating but in the way that she

has been taught to communicate. Maybe it was a coincidence that Jensen used the

genders in such a way for this example, but by doing so it makes it harder to

see whether the wife communicates in such a way because she was raised working

class or because she has been socialized to be a connected/emotional

learner/communicator because of her gender.

Just

some things to think about! I did enjoy this text. So far this is my favorite

reading of the semester.

Work Referenced

Belenky, Mary F.,

Blythe McVicker Clinchy, Nancy Rule Goldberger, and JillMattuck Tarule.

"Procedural Knowledge: Separate and Connected Knowing."Just Methods: An

Interdisciplinary Feminist Reader. By Alison M. Jaggar.Boulder, CO:

Paradigm, 2008. 235-47. Print.

Jensen, Barbara.

Reading Classes: On Culture and Classism in America. Ithaca: ILR,2012. Print.

Kelley, Robin D. G.

Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the GreatDepression. Chapel

Hill: University of North Carolina, 1990. Print.